The term “Asian art papers,” as used here, means the painting papers made in China, Japan and Korea for ink/brush painting. These papers are made from a great variety of plant fibers, such as bamboo, mulberry bark, cotton, hemp, linen and rice straw (dried stalks of the rice plant). Perhaps it was the rice straw paper that gave Westerners the idea to describe all Asian painting papers as “rice papers.”

Asian painting papers come in various thicknesses and sizes, and have different degrees of absorbency, created by adding sizing such as starch, alum, glue or gelatin in the manufacturing process. The sized papers give artists more control; therefore, they’re more suitable for a detailed-style of painting. Unsized papers are very absorbent and, therefore, are more suitable for a spontaneous and expressive style of painting. Semi-sized papers fall between the other two levels of absorbency.

The best and most desirable paper for Chinese ink/brush painting and calligraphy is Xuan (also “Shuan” or “Shuen”) paper. It was originally made in the Xuan County of Anhui Province in Southern China. The main ingredient was the bark of blue sandalwood, to which other fibers, such as mulberry bark, bamboo, hemp, linen and rice straw, might be added. Now any paper that is made in a similar manner is called Xuan paper, regardless of where it’s manufactured.

Chinese masters prefer single (one-ply) Xuan paper because this somewhat translucent material has a smooth and sensitive surface that’s receptive to brushstrokes. The paper also allows for vivid colors and exquisite ink tones, although the smooth, thin surface makes inks and watercolors harder to control. Double (two-ply) Xuan paper is slightly thicker, which allows for easier control of inks and watercolors; therefore, it’s more suitable for beginners. Sized Xuan paper is much less absorbent than the unsized version, so the sized paper is most suitable for a detailed-style of painting.

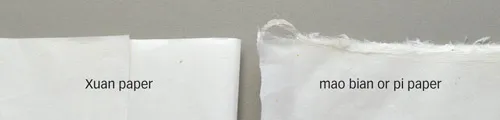

Because Xuan paper is made with short fibers, it has an exquisite, fragile quality and easily falls apart when wet. This paper must be handled with care.

On the other hand, Chinese mao bian (hairy-edged) paper, is made with longer fibers that you can pull from the paper’s “hairy” edges. The longer fibers add strength, so the paper won’t fall apart when wet. For this reason, mao bian paper is also called pi (skin or leather) paper.

Comparison of paper fibers: Short-fibered Xuan paper has a clean edge, smooth surface and fragile consistency. Long-fiered mao bian or pi paper has a “hairy” edge, coarsr texture and relatively strong consistency. Both are Chinese papers.

The Japanese papers best known to Americans are the following:

Masa paper is machine made from sulfite pulp (the almost pure cellulose fiber produced by what is called “the sulfite process,” which involves the use of sulfite and salt), is heavily sized and very strong. I use it for my crinkled paper technique and also as a backing sheet on which to paste paintings done on fragile paper.

Kozo paper is handmade from long kozo fibers. It’s lightly sized and very strong. I used it for ink/brush painting, mono-printing and marbleizing.

Mulberry paper is handmade from mulberry fiber and sulfite and is very strong. I use it for ink/brush painting.

Kinwashi paper is machine made from Manila hemp embedded with short fibers. This paper is generally intended for decorative use; I use it occasionally for painting because of the added interest of the embedded fiber.

Overall, Asian painting papers, regardless of the manufacturer, thickness, size of sheet or absorbency, are much thinner and more delicate than Western watercolor papers. —Cheng-Khee Chee