Given how closely Chinese calligraphy is intertwined with Chinese history, culture and literature, growing up I’ve heard many tales of historic calligraphy masters that have captured my imagination. A handful of the stories stayed with me over the years, their imagery popping up from time to time to inspire and nudge me further along my calligraphy journey. And today I’ll share my favorite 3 with you, in the hopes that they’ll work their magic on you, the same way they did on me.

Calligraphy strokes that penetrate wood planks

Say what? If you’ve been following this series, you’re probably already familiar with Wang Xizhi, commonly known as the best Chinese calligrapher throughout history, and whom I’ve mentioned a handful of times. One of his tales goes as follows:

One day, he wrote some calligraphy on a wood plank, and handed it over to a carpenter to carve out accordingly. But when the carpenter started chiseling with their knife, they noticed that Wang’s strokes had already penetrated the wood by about 1 centimeter. This incident shocked the whole city, and turned into a common four-word idiom, 入木三分(pronounced as “ru mu san fen”, which means to penetrate the wood by 1 centimeter). This idiom is now used more generally to praise a well written article or speech. But in the context of Chinese calligraphy, it reminds us that the strength of the strokes is a crucial element to mastering this art form. When I was young, aside from wishing that I could fly, or create power balls in my hand, I also dreamed of one day being able to channel enough energy through my calligraphy brush to leave a dent.

Pollution or dedication?

臨池學書(pronounced as “lin chi xue shu”, which means to practice calligraphy by the lake). Written in Cursive Script.

During the Hang Dynasty, an aristocrat went to visit his friend Zhang Zhi. As he was approaching his destination, he passed by a lake with pitch black water. Tattered rags covered trees nearby, and his friend sat beneath the rags, absorbed in his calligraphy practice. The aristocrat snuck up from behind, wanting to see what Zhang Zhi was working on. It was such a master piece, that the aristocrat couldn’t help but say, “Bravo!”. That shocked Zhang Zhi out of his trance, and upon seeing his friend, said, “There’s no need to praise me. I had to exchange a whole pond of ink water for these few lines.” Only then did the aristocrat realize that over the years, Zhang Zhi practiced on the cloths and washed them in the lake, which stained the lake black.

It’s probably best not to copy the exact same behavior, as a lake stained with ink water is most likely detrimental to both the environment and the creatures within. However, there’s nothing wrong with admiring the dedication and work ethic. There is one aspect of the story that is environmentally friendly and worth emulating — the reusable practice material. You could use a normal cloth, or check out one of the magical, reusable water Chinese calligraphy cloths. This story also resulted in a four-word idiom, 臨池學書(pronounced as “lin chi xue shu”, which means to practice calligraphy by the lake).

Duck, duck, GOOSE!

We have another story about Wang Xizhi. Wang is known for his love of gooses, as he loved to observe the way they move. One time, Wang overheard that an old lady owned a big white goose. He paid the old lady a visit, but she wasn’t home at the time. He did see the goose though, and immediately fell in love with it. He asked the neighbors to help inform the old lady that he would return again the next day. The old lady, unaware of Wang’s intent, and wanting to be hospitable, killed and cooked the goose for Wang’s visit. You can probably predict Wang’s reaction to that.

Wang loved observing gooses, as he got a lot of his inspirations for calligraphy from them. He thought when one holds the brush, the hand and fingers, in particular the index finger, looks very much like a goose’s head.

Index finger looks like a goose’s head (Image Source)

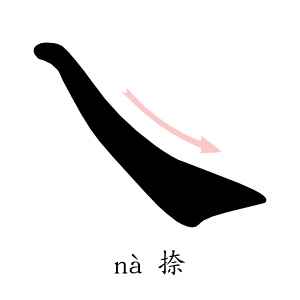

Other scholars also speculate that, when a goose paddles, the motion is similar to writing 捺 (pronounced as “na”), one of the eight basic strokes. The feet start off shallow, continue deeper into the water, then slowly lift back up.

捺 na, one of the eight basic strokes

That’s a wrap of the 3 stories. Have they made you want to practice more? Don’t be afraid to seek your own inspiration as well. For instance, I’m a big fan of basketball, and particularly love watching Steph Curry’s elegant shooting strokes. I find them not at all dissimilar to calligraphy strokes. Steph Curry is my modern day goose ⛹️ 𓅬 And thank goodness no one would ever cook up Steph for my sake! Come back in a month’s time. We will learn more about historical and modern day Chinese calligraphy masters then.