In the previous post, we learned about what the different styles are. And in this post I’m going to share practical tips on how to start learning and practicing these styles. I divided the 5 styles into two separate posts, and in today’s part one, we will cover Regular Script, Semi-Cursive Script and Grass Script.

Regular Script is the best style for beginners to start with, as the strokes and structure of the characters serve as foundations for both Semi-Cursive and Grass Scripts. Even though the techniques for Seal Script and Clerical Script are somewhat independent from Regular Script, since Regular Script is the script that’s used in modern days, it’s more practical to start with if you are completely new to Chinese calligraphy. It is the only script whose characters most mandarin speakers can easily identify. And once you are adept at writing Regular Script, it’s a natural progression to move on to Semi-Cursive Script, and then Grass Script, where the strokes and characters flow and connect more smoothly, and certain structural constraints are loosened.

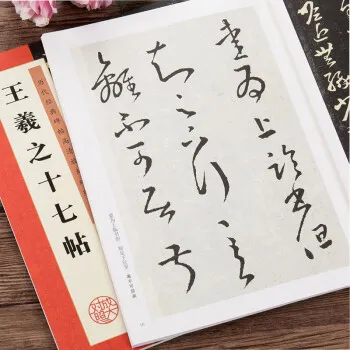

帖子 Copybook

Typical look of a 帖子/ copybook

Before we delve into each script, I’d first like to introduce the concept of 帖子 (pronounced as “tie zi”, meaning copybook or transcription). Like the learning of most crafts, one starts learning Chinese calligraphy by copying the works of one’s calligraphy teacher, or of works written by the most accomplished calligraphers in history. There’s a formal term for this act of copying, called 臨摹 (pronounced as “lin mo”, meaning copy).

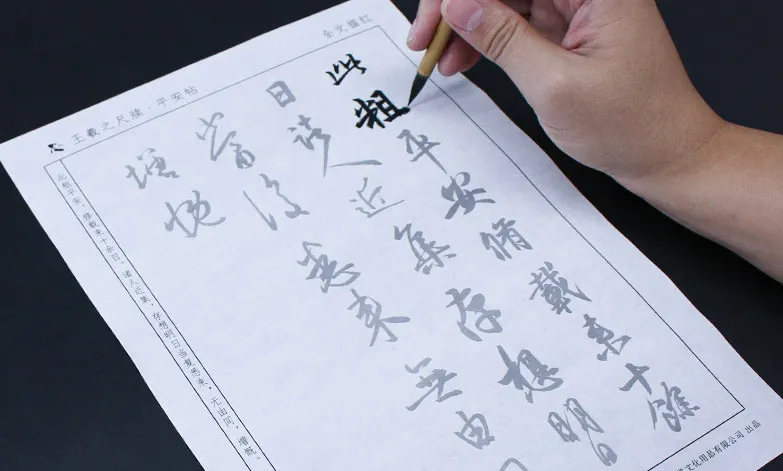

When starting off, if you have access to them, it’d be ideal to buy practice booklets with faded prints which are designed for you to write over them, like the one shown in the picture below. But don’t fret if you can’t find them. Don’t be afraid to put your practice paper directly on top of the copybooks so you can trace over the words. Or if you’re worried about staining the books, make printed copies of them before doing so.

Practice booklets with faded prints

As I go over each script in the following sections, I’ll share more information on the best copybooks to start with for each script, as well as other practice tips.

Regular Script

If you haven’t already, make sure to check out the third post in this series, which teaches the 8 basic strokes in Regular Script. It would be ideal to have a good grasp on them before you proceed with practicing whole characters from copybooks.

There are four most notable Regular Script calligraphers in Chinese history — 歐陽詢 (Ouyang Xun),顏真卿 (Yan Zhenqing),柳公權 (Liu Gongquan),and 趙孟頫 (Zhao Mengfu)。The former three are calligraphers from the Tang Dynasty, and the last, Zhao Mengfu, from the Yuan Dynasty. They are commonly referred to as the “Four Masters of Regular Script” (楷書四大家), and you can pick any of their works to start learning from.

This Wikipedia page lists the four masters, along with the names of their greatest works, which are surrounded by 《…》at the end of each list item. You can copy and paste either the calligraphers’ names, or the names of their works into Amazon, and both provide a decent number of copybook selections to choose from. Don’t worry even if you can’t get them or if they are over your budget — the results of performing a quick Google image search on these titles would be enough to get you started.

Whether you are working with an image or a copybook, make sure not to rush through it, and take your time practicing and perfecting each character. If it’s your first time, it’s common to need to write a single character at least a dozen times before moving on to the next one. In Regular Script in particular, a lot of emphasis is put on perfecting each stroke, as well as the composition of and relative positioning of strokes within a character. In my own learning journey, oftentimes my teachers didn’t let me move on from a copybook until I had worked with it for a year or more. And it was only about 5 or 6 years into practicing calligraphy and Regular Script, that I was finally allowed to start dabbling with Semi-Cursive Script, which we’ll cover in the next section.

Semi-Cursive Script

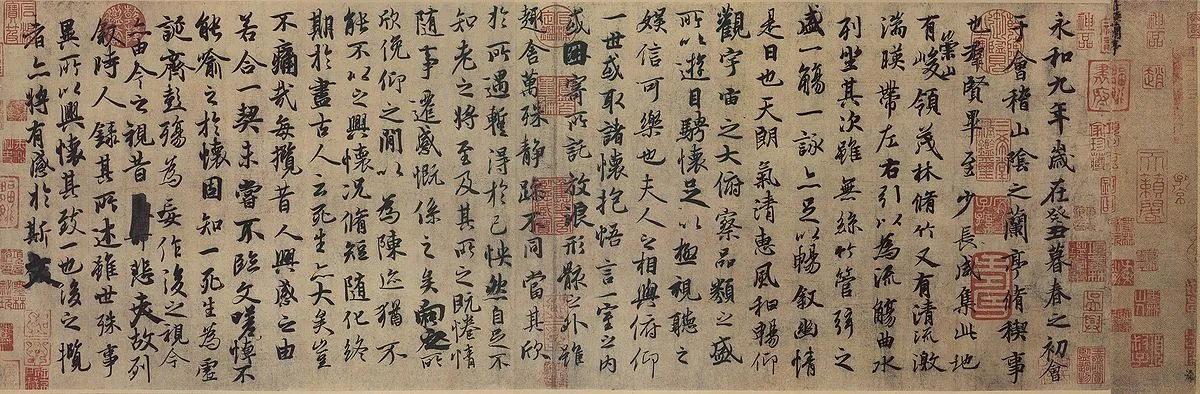

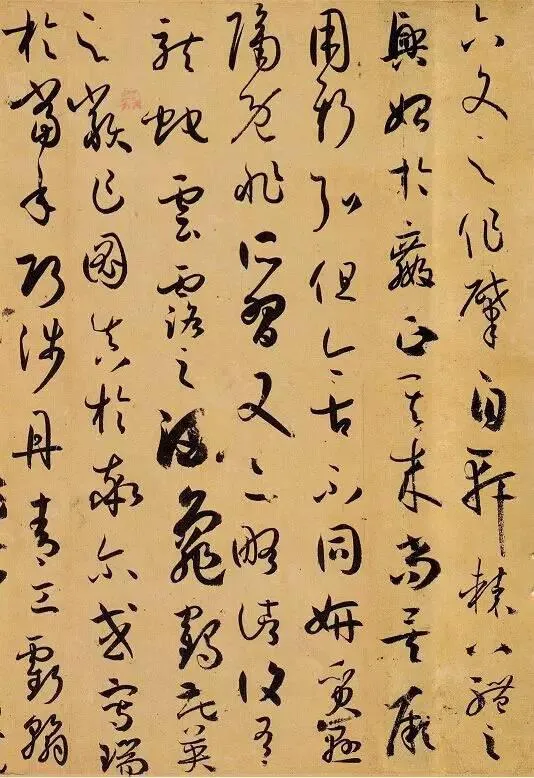

Lanting Xu by Wang Xizhi

Once you have a good grasp of Regular Script and are ready to get a bit more flowy, there’s no better place to start than calligrapher Wang Xizhi’s Lanting Xu. Not only is Wang Xizhi commonly known as the best calligrapher in all of Chinese history, this work in particular is termed the “first of all Semi-Cursive calligraphy works under heaven” (天下第一行書).

When first starting off with the Semi-Cursive Script, pay attention to each stroke (the beginning, ending, and thickness and curves in between), and observe how they differ from Regular Script. Additionally, take careful note of how the various strokes are connected, which types of strokes usually have linkage and which don’t, and how certain groups of strokes are combined and reshaped to increase speed and smoothness. The connecting strokes are usually thinner than the main strokes, though that’s not necessarily always the case, and they are also not uniform (there’s often changes in thickness and angle within one connecting stroke).

This is a lot to take in all at once — and don’t be alarmed if you feel overwhelmed initially. I recall feeling a bit tricked when I first started practicing Semi-Cursive; the promise was a smoother and faster writing style, but why did it seem to take more time, and is more complicated than the Regular Script? The speed will come with time and practice. Like with just about everything related to Chinese calligraphy, patience is key.

When you are still at the beginning stage of learning the various aspects of this new script, it’s alright to still write with gridded practice paper. But I’d recommend moving on to proper xuan paper as soon as you feel comfortable (for more information on these different types of paper, visit the second post of this series), as a lot of Semi-Cursive Script (and Grass Script as well) is about the relative positioning and spacing between characters.

Some other great Semi-Cursive Script calligraphers or works you can learn from are calligrapher 米芾 (Mi Fu)’s works, as well as 趙孟頫 (Zhao Mengfu)’s 前後赤壁賦 (Former and latter Ode on the Red Cliffs).

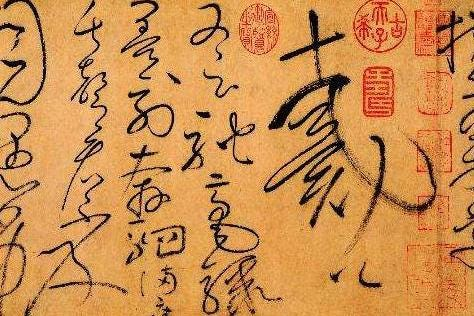

Grass Script

One thing to keep in mind before we go on, is that here I am summarizing at least a couple years of practice into a few paragraphs. There’s no harm with jumping ahead and dabbling with these different scripts for fun, but it’s important not to lose sight on the limitations that comes with attempting to run before knowing how to walk properly.

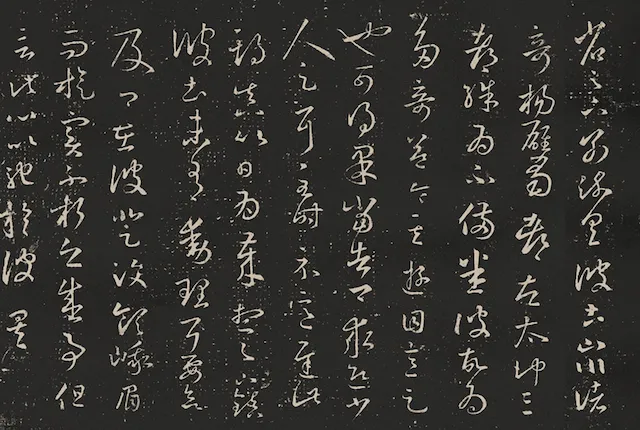

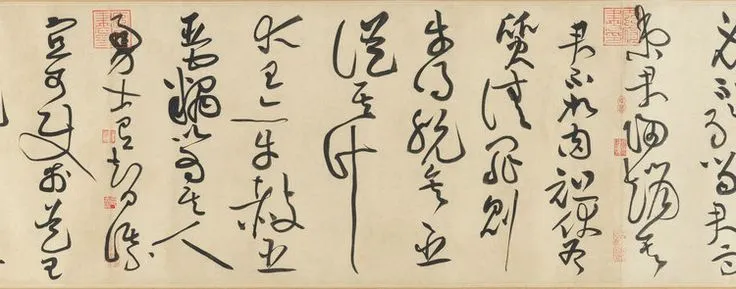

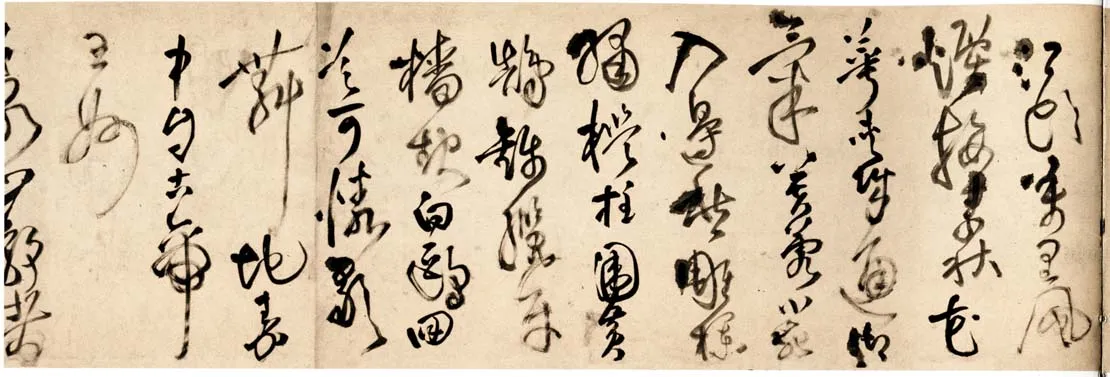

So, once you feel confident about Semi-Cursive Script, it’s time to try out Grass Script, which is even more fluid and succinct, to the extent that most mandarin speakers actually have trouble recognizing the characters. A few iconic copybooks that are great to start with:

- Seventeen Engravings (十七帖) by Wang Xizhi (王羲之)

- A Narrative on Calligraphy (書譜) by Sun Guoting (孫過庭)

And for Grass Script works that intentionally push past the boundaries of traditional word structures and composition, and involve not just the variation of strokes but the wet / dryness of it as well:

- Bibliographies of Lian Po and Ling Xiangru (廉頗藺相如列傳) by Huang Tingjian (黃庭堅)

- Works by calligrapher Wang Duo (王鐸)

- Autobiography (自敘帖) by Huaisu (懷素)

That’s a wrap on part one of styles deep dive. Even though I’ve been at it for over 20 years, preparing this post made me realize how much is still out there that I haven’t yet practiced or mastered. And I can’t wait to re-familiarize myself with many of these masterpieces! Hope you’re as excited as I am, and ready to explore this abundant and magical tradition that is Chinese calligraphy. And there’s more — I’ll see you again next month when we learn about the remaining two scripts, Seal Script and Clerical Script.